Accounting for NFTs: Key Components & Challenges

Digital assets are mistrusted by many accountants. They are, however, fundamental to the growing Web3 vision of the internet, e-commerce, and peer-to-peer transactions. And Accounting for NFTs is vital to achieving errorless accounting for digital assets. Moreover, it can prove that a person owns tangible, intangible, and digital assets.

NFTs are useful for much more than just purchasing and selling pixelated JPEGs. For instance, they can be used by musicians and visual artists to sell their work directly to followers. Many venues are also selling NFT tickets for shows.

Many start-ups and other “digital native” businesses are already looking for CFOs, auditors, tax experts, and accountants who can assist them in correctly recording and accounting for NFTs and other digital assets.

Let’s deep dive and explore the vital aspects of NFT accounting!

How Does NFT Make Money & Add Value?

The ability for musicians or visual artists to receive royalties each time their work is used is a classic example of NFTs producing taxable income and providing value.

Otherwise, artists currently receive nothing for resale. NFTs, on the other hand, offer an immutable, cryptographically secured Web3-enabled code that monitors the usage of the creative work and pays the artist for each instance in which it is used.

The time of “minting,” or creation, establishes these rights and procedures. It is possible to estimate the worth of this type of NFT by adding the value of the accompanying music, artwork, or other material to the amount of future financial statements (i.e., royalties) from the NFT for viewing and playing.

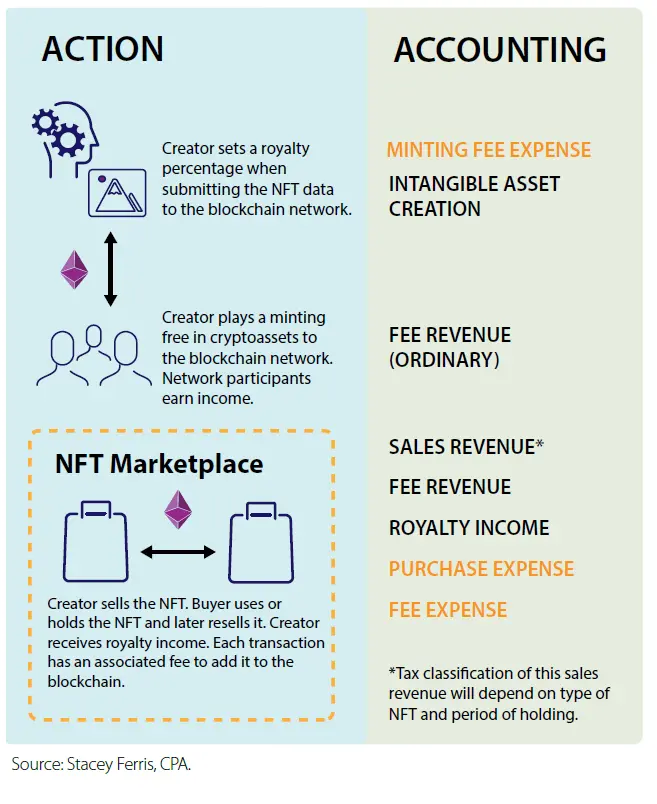

How Do NFTs Generate Accounting Events?

Why is Accounting for NFTs Difficult?

U.S. GAAP does not provide any guidance regarding the accounting treatment for NFT. Because of their extreme volatility and speculative nature, digital assets provide a problem for an intangible accounting approach.

What are the key Considerations While Accounting for NFTs?

Difficult Revenue Recognition Due to Varied Ownerships

Many times, businesses offer NFTs for sale on online markets like OpenSea or Magic Eden. These markets serve as a middleman between NFT producers and consumers. To identify the principal and agent in these situations, the parties must ascertain who has control of the NFT at the time of sale to the end user.

The creator is the transaction’s principal if they retain ownership of the NFT before giving it to the end user. When the creator is the principal, they separately recognize the cost of the fees paid to the marketplace to effectuate the transaction and gross revenue in the amount paid by the end-user.

In order to facilitate the transaction between the creator and end-user, the marketplace, or the agent that facilitates the transaction, recognizes income depending on the sum received from the creator.

However, the market becomes the primary if it is in charge of the NFT. At the same time, it is transferred to the end user. When a marketplace acts as the principal, it recognizes gross income based on the amount paid by the end-user and costs based on the amount given to the creator in a separate transaction.

Instead of the final user’s gross payment, the creator will record revenue depending on the amount obtained from the market.

The ASC 606 – Revenue Recognition standard must be considered when determining whether the revenue reported from an NFT transaction is subject to it. Creators who sell NFTs are parties to a contract with the end user.

The sale of NFT is a typical business activity for the creator. The creator must take into account the following five factors when assessing NFT revenue under ASC 606:

- Name the contract

- Find the contract’s performance requirements

- Establish the transactional cost

- Distribute the purchase price

- Revenue is recognized when or as soon as performance commitments are met

All NFTs are not created equal, while others may function as subscriptions granting the owner the ability to access paywalled content or attend closed events.

Creators must consider each NFT or NFT project separately when they assess the aforementioned ASC 606 standards. These factors apply to royalty and primary revenue. Secondary sales may occasionally be even more significant than primary sales.

Damage & Fair Value

NFTs are well-liked, but their “non-fungibility” (or “uniqueness”) also makes them challenging to value. Each NFT has a different value depending on its unique characteristics, scarcity, and distribution method.

A deal between a willing buyer and seller establishes the NFT’s value. This exchange frequently involves digital currencies like ETH or SOL. The fair value of the cryptocurrency at the time of the transaction can be utilized to determine the initial value of the NFT when cryptocurrency is exchanged in the transaction.

For instance, if you purchase an NFT per 2 ETH for $1,500 for ETH, the NFT’s initial worth is $3,000. The value of the NFT remains unchanged even if the price of ETH drops to $1,000 following the transaction. After the original transaction, it must be priced separately, regardless of the cost of ETH.

The most challenging aspect of this procedure is the constant appraisal of NFT. Due to the fact that the sector is still in its infancy, there aren’t many businesses that specialize in NFT value. Finding sales of comparable NFTs on the market is one option.

NFTs can be distinctive, particularly when it comes to digital art. There might not be a helpful price comparison accessible. As of right now, there is no clear GAAP guidance on how to handle NFTs or the proper valuation approach.

NFTs come under ASC 350, Intangible – Goodwill and Other: Assets (not including Financial Assets) that lack physical substance, according to GAAP. The holder must decide whether the NFT has a finite or unlimited life under ASC 350. For instance, NFTs made for digital art will probably have an endless lifespan.

According to ASC 35-30-35-4, an intangible asset should be categorized as an indefinite-lived asset if there are no limitations on the useful life of the asset to the reporting entity due to legal, regulatory, contractual, competitive, economic, or other circumstances.

Intangible assets with an indefinite lifespan are exempt from amortization. However, it’s also critical to remember that the market for digital assets is unstable and that prices can shift dramatically in a matter of seconds.

The price the last buyer paid for the NFT can be used to estimate its worth. But if the NFT is determined to be an indefinite-lived asset, the next buyer may be ready to pay less, which would be a sign of impairment. Again, the popularity of NFT also makes it challenging to assess for impairment.

Amortization

Companies may decide that the life of their NFTs is limited. They also must take into account the length of time the NFT will contribute to their cash flow while making this decision. In addition, the NFT will likely be categorized as a finite-lived asset if the corporation determines that the cash flow of the NFT has a foreseeable limit.

An NFT that allows users to have digital accessories in a game, for instance, is likely to have a predetermined upper limit on its cash flow because games age over time as players move on to the next big thing. The same may be said about NFTs that allow users access to a particular event.

Companies must amortize NFTs based on their useful lives when categorized as assets with finite lives. The amortization will reduce the intangible asset’s value on the balance sheet and cause an expense to be recorded in the income statement.

Organizations can choose the amortization methods that best suit their circumstances. Companies must understand the following before determining the asset’s useful life.- NFT’s purpose

- End-user target

- Rights that are transferred to the end-user

- Projected future cash flow the NFT will produce

- Estimate life of intangible assets according to FASB ASC 350-30-35-3

Price & Possession

Companies must decide how to account for the cost of generating NFTs in addition to revenue, valuation, and amortization. NFT development expenditures typically pertain to digital rights rather than physical property. So, they will mostly not be covered under ASC 330, Inventory.

The majority of the time, expenses related to creating NFTs will fall under one of the following GAAP codifications:

- Internal-Use Software (ASC 350-40)

- Costs of Software to be Sold, Leased, or Marketed (ASC 985-20)

Whether or not the final program will be owned by the end user will influence which codification to employ.

The ability to use digital objects in the metaverse, such as games, is granted by some NFTs. Only the developer’s servers host these things, which are only available online. In this case, the software is not in the end user’s ownership. As a result, the NFT development costs would probably be covered under ASC 350-40.

Certain expenses incurred during the creation of the NFT are capitalized in accordance with ASC 350-40. The costs associated with building the NFT would fall under ASC 950-20 if the end-user already possesses the software at the time of the NFT acquisition.

The majority of expenses made while developing the NFT are classified as research and development expenses under ASC 985-20 until the technology is completely developed. These expenses will be deducted when they become due.

To make the right determination on cost treatment, companies need to have a good understanding of the following:

- NFTs that are being developed

- Rights that are being transferred to the end-user upon purchase

- Intellectual property being developed

- Different costs being incurred during the development process

Do You Find Accounting & Auditing NFTs Challenging?

Don’t worry. We’ve got you covered! Our team of experienced accountants at Mesha is here to help with our well-designed processes and modern NFT accounting software. So let us take care of the complex work while you relax, and know that we’ll help you minimize taxes and capture all the revenue you are owed.